LAEL WILCOX: TOUR DIVIDE

You’d be forgiven for fancying a bit of time off the bike if you’d just completed a 1700km bikepacking race through Kyrgyzstan. Put your feet up, maybe. Chill out. It’s what most people might do in that situation... Lael arrived in Scotland late the night before, after a hectic few days post Silk Road Mountain Race, including a flying visit to Eurobike. We are in a rented cottage, just outside of Aberfoyle and instead of chilling out, Lael is kitting up to go for a recce ride of the Duke’s Weekender course. She’s fizzing with energy while sampling some of Scotland’s finest delicacies in the kitchen before we leave. Irn Bru and Tunnocks might not be a typical racer’s diet, but as I’ve already worked out, Lael isn’t a typical racer.

It’s a mark of how segmented cycling has become that you’d be forgiven if you haven’t heard of Lael Wilcox. You won’t find her lined up at a UCI World Cup XC race, or a round of the EWS. Equally, she doesn’t make up part of the peloton in the pro road scene. If your chosen niche of riding is ultra-endurance events, though, her name tends to elicit hushed tones and a sense of awe. Lael races across entire countries and continents. She’s the rider who appears to be constantly smiling while doing so, who never appears to be tired while those around her eventually drop. She frequently wins, often outright, beating male competitors.

Lael probably first came to wider prominence in 2016, when she won the Trans Am race – cycling from the west coast to the east of America. She averaged 235 miles per day for 18 days, sleeping less than five hours each day. On the last day, Lael rode into first place, passing an exhausted Steffen Streich. He had recently woken, and in a still sleep-deprived state, set off riding in the wrong direction. Realising his mistake as she passed, he swung round and joined Lael. “Why don’t we finish together?” he suggested. Lael smiled and simply responded, “this is a race” and accelerated away with all her might. She chuckles as she recalls the story, but in the highly unlikely event that I’m in the same position, I’m very aware that it would be unwise to repeat the question.

Lael hadn’t exactly come from nowhere. She had set the women’s record on the Baja Divide and Tour Divide the year before, but it’s still a rarity to see a women win races outright. The world of ultra-endurance appears to be something of a leveling ground across genders. Outright power and strength counts for much less in comparison to the ability to endure for days on end. Male entries massively outweigh those from females, but things are changing. And as they do, more and more women are demonstrating they won’t just compete at the sharp end, but will win as well. Lael sits right at the front of the new guard. It’s a position that she seems very comfortable in.

We saddle up and spin gently along the road towards Aberfoyle, a cool wind blowing, carrying with it the first signs of autumn. Conversation isn’t so easy on the narrow, but relatively busy road and we grab snatches of chatter before singling out to allow cars to pass. Is she not tired after Silk Road? Now, over a week on, then not so much. The deep post-race fatigue has gone, but she isn’t hurrying back into hard training – not that Lael seems to follow a classic training schedule anyway. She just rides. A lot, a long way.

And how was Kyrgyzstan? “Wild, tough, beeeeeautiful”. It’s hard to get a true sense of the scale of the race from Lael’s description. Her legs felt good for the duration (Lael finished in 7 days, 15 hours, and 23 minutes – she was the second rider back and first female) and there were no specific challenges. Her tales are of the occasional meetings with horse riders, and simply enjoying solitude on the trail for a few days.

Silk Road is a little more than a 1700km spin in the mountains though. As with most of the races Lael chooses to enter, it’s a self-supported event. The clock does not stop, there are no stages. You just ride until you reach the finish, resting when you need to. Riders are not allowed any outside assistance – no friends driving up the road, no stashing supplies beforehand. You can visit shops to buy food and/or spares… assuming anything is available. The remoteness of Kyrgyzstan is very different to cycling across America. Food was occasionally a challenge, but Snickers and fried bread kept her going. It doesn’t pay to be a fussy eater when your body is craving calories.

Each night, Lael would roll out her sleeping mat, lightweight sleeping bag and bivvy. She’d climb into a down suit to boost the warmth in sub-zero temperatures. Waking at 2am each morning, she would ride the first few hours of the day in her down suit, under the stars.

Finally off the road, we were able to ride side-by-side along the edge of Loch Ard. Forest and fell feel like a long way away from Asia, but this corner of Scotland is beautiful. We enjoy an illusion of remoteness in comparison to the true wilderness of the 4000m passes that Silk Road crossed.

Our conversation ebbs and flows with the gentle contours of the lochside trail. It wanders to how we started riding. There was no youth camp, or competitive structure to Lael’s early riding. A bike was simply a tool for travel – albeit a fun one. Her first “long” ride happened when she didn’t have the fare for the bus one day, so rode from her home to work in Seattle. The journey of 70km or so awoke a realisation in her though. If she could ride that far, then she could ride anywhere. The following years were spent cycle touring with her then partner; covering big distances, but with no real urgency.

The couple were in Israel when Lael entered the Holyland Bikepacking Challenge. The bug had truly bit and she raced the 2015 Tour Divide a few months later (winning the women’s race).

We try to dissect what attracted Lael to cycling rather than running or climbing or any other way to explore the outdoors. It’s an impossible question to answer, but we come round to the ease of movement – covering ground in a way that allows you to travel huge distances in a manner that allows you to enjoy where you are. It’s strangely reassuring to hear that someone who is at the pinnacle of what is achievable on a bike gets the same fundamental joy out of riding that you or I might. There is no doubt that Lael would be riding whether she was winning races or not. She describes racing as her way of taking breath. It’s the period of calm for her in between the rest of life. It’s an amazing way of describing competition and she makes it sounds almost meditative.

There’s actually a quietness to Lael’s energy. Her eyes light up when she talks, and slings her head back when she laughs and tells stories with ease, engaging you from the first sentence. She doesn’t dominate, though. Equally as keen to listen and ask questions, she pauses in response, digesting your reply. It’s disarming and a refreshing change from the personas of better known sports stars – a counter to the argument that you need to channel arrogance and selfishness to achieve success.

Listening to Lael speak is deeply inspirational, bringing the apparently impossible down to a feat that feels achievable. When not racing or travelling, she teaches children about biking, fuelling their enthusiasm for being outdoors. Every now and then though, she drops in a sentence that reminds you that “ordinary” and “achievable” are very different for Lael. Back to the Silk Road. On the final two nights, she slept for two hours a night, from 20:30 to 22:30. Then, on the final night, she just wanted to get it done, so took an eight minute nap… helmet and shoes still on, before getting up and pushing on. She crossed the finish line with slightly twisted bars. They’d been like that since a small crash a couple of days earlier, but Lael the racer never wanted to take the time to straighten them.

In fact, Lael doesn’t come across as a gear freak. She just wants kit that is practical and reliable. While some took gravel bikes to Silk Road, she chose a mountain bike with 2.3in tyres. It meant she could ride across the roughest of the terrain on the route. It was simply faster overall.

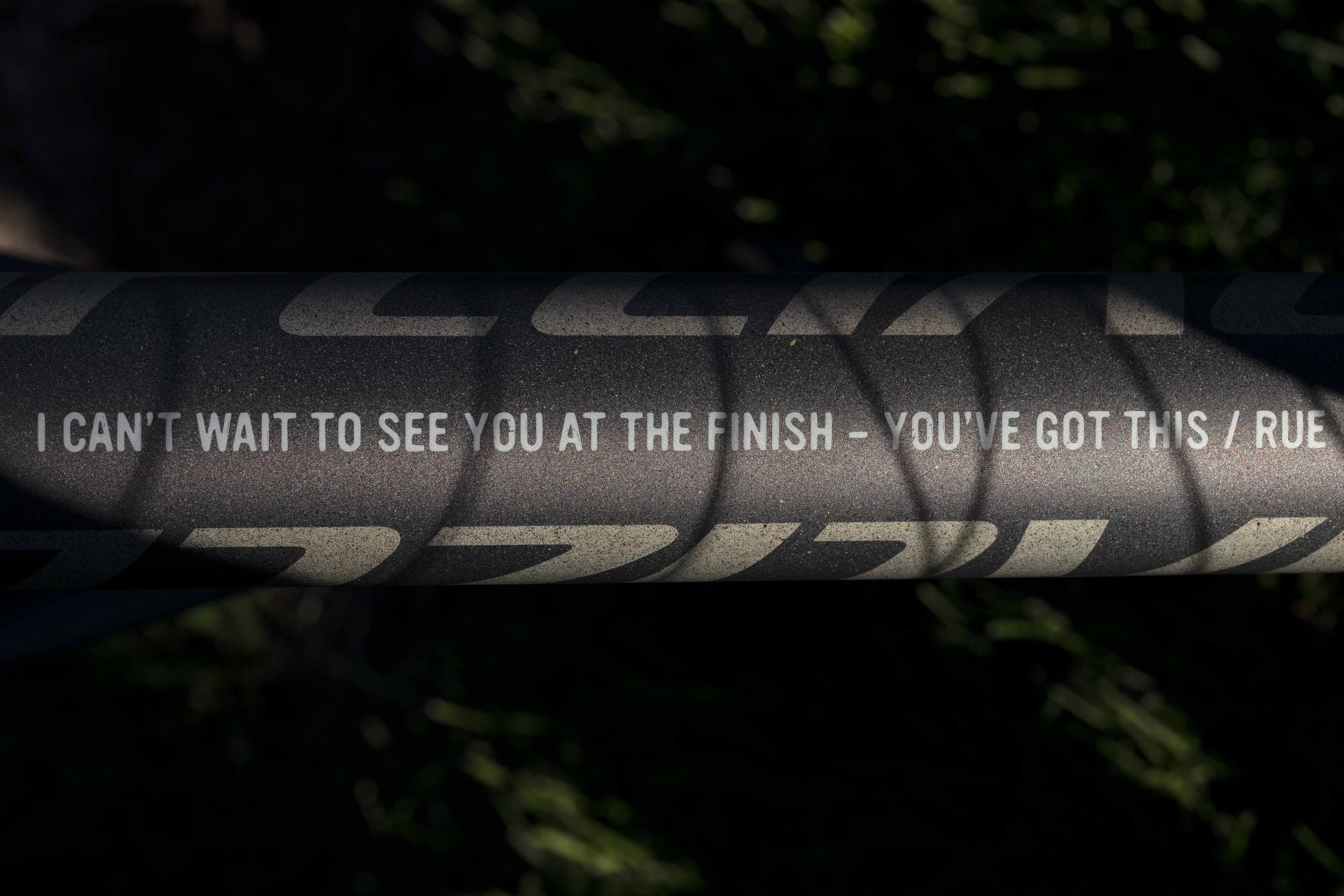

We loop back around to the cottage. Lael’s partner, Rue is there, laptop open. She’s making edits to her film about this year’s Tour Divide. It was to be the story of Lael’s attempt to win the race outright on the route that runs from Canada all the way down to the Mexican border. Things didn’t go to plan, and eventually Lael withdrew from the race, in the midst of a public argument.

The controversy is another story, and one that has been well told by Rue in the film and articles for The Radavist. In summary, though, a few people took issue with Rue filming on the race route, arguing that this would constitute outside assistance and unfair advantage. This was despite specific measures the crew put in place (including Rue ensuring Lael didn’t see her during the race).

Some of the resistance is as a result of a wider challenge that bikepacking racing is facing. As its popularity grows, it is possibly alienating some of those that were first attracted to it precisely because it was uncommercial, underground and uncovered. Racers like Lael bring an increased awareness of and focus on that world. The best racers are often sponsored and as part of that agreement have a natural desire to tell their stories and promote their achievements. In doing so, more people are hopefully inspired to ride, yet the pay-off is maybe the evolution of some events.

It’s a subject that both Lael and Rue talk sensitively and intelligently about. There isn’t a simple answer to the challenges of covering these kind of races. Both are passionate in their argument that they should be documented though. There needs to be visibility of people doing these things, particularly women. How can you be inspired if you don’t know something is happening?

Regardless of where you stand on the argument, Rue and Lael bore the brunt of condemnation by a vocal minority of people. In the end, Lael scratched, met with Rue and hugged her, then carried on the ride. It was a hurtful episode, made worse by the hypocrisy of some of the commentators.

The result, though is perhaps a stronger film than if Lael had just raced all the way to Mexico. As the title suggests, and a single day with Lael confirms, she just wants to ride. You have a feeling that she will continue to ride, and inspire as she does so, for a long time to come.

As I get ready to climb in the van and head home, Lael and Rue pull on running shoes, keen to grab the last thirty minutes of daylight on offer. Lael, never not active. The clouds are already tinged orange as they set off, both smiling and seemingly re-energised by being outside.